The all-purpose heavy duty Climate Chaos thread (sprinkled with hope).

Comments

-

Lerxst1992 said:Bri, definitely agree with "A child born in 2020 will face a far more hostile world that its grandparents did,” but I disagree we are past the point of no return.

But....we need to end coal now, which may be near impossible. When I talk to independents (those lovingly gas price voters) that's really one of two points that I tell them matters (the other being trump is a murderer of Americans).

So forget electric cars, that tech is at least a decade away from doing anything. This species needs to end coal now.

Yes, ending coal would be a lot of help.

As far as being past the point of no return for global warming (and I would imagine the author means in terms of human time- who knows how many cycles of warming and ice ages the earth has left over the next 4 billion years), I really don't know if anyone knows for absolute certain. I wonder though, if you could anonymously poll the top 100 climate scientists in the world and ask them to honestly say whether or not we have passed that point, what would that poll indicate?Regardless, of course, what is clearly evident is that we need to start acting now. I get discouraged at time like this morning where, when I went to meet some friends in town this morning the only place to park was next to a pickup truck that was too large to fit into a standard parking space (and too clean and shiny to be a work truck). Fortunately, my car easily fit into the crowded space next to it.

Does anyone really need this?

"It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0 -

I see your point, but in reality you have absolutely no idea why this person has the truck or what it’s used for.

So maybe he does need it.0 -

hedonist said:I see your point, but in reality you have absolutely no idea why this person has the truck or what it’s used for.

So maybe he does need it.I totally agree with you. But also understand this, I live in a very redneck (I can say that- I know some rednecks I would call good friends) country and a lot of these guys are cowboy wanna bees who drive their ROATs (ridiculously oversized American trucks) as commuter vehicles, not as work trucks. My own wife has a large SUV. She doesn't use it much these days now that she let the bookstore go, but many, many times in her 38 years as bookstore owner, she hauled large quantities of book for the store. You're not goin to be able to do that in a subcompact. It was basically a work truck.

For several of the nearly 20 years that I worked at that bookstore on Main Street, I had a leased parking space near the post office that was wedged in between two of these kinds of behemoths. Those two monsters were driven by two guys who also worked downtown- one in a small art gallery, one in an office above a store, and in all that time, I never saw either of them haul anything in the vehicles beside their own fat asses- not even another passenger. The beds of the trucks had nary a ding. Those were commuter vehicles, not work trucks.But I also know a number of people in this area that have large pick ups and use them for what they were intended- work vehicles. Plumbers, electricians, contractors, carpenters, handymen and handywomen, gardeners and landscapers, HVAC people. I personally know at least one such person in our area and, of course, they use pickup trucks.

I don't know about the person I was parked next to today and I won't guess. My comment is more generalized. I know for a fact that a good deal of the large pickup trucks driven is this area are not work trucks. It's a thing here. An insecure macho thing.

In the age of climate change and global warming, I am going to occasionally make remarks about that kind of activity, not to offend anyone personally, but as a general statement. And I stand by my words on this one."It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0 -

See! Again, missing my joke... Trying harder? That's funny.mickeyrat said:tempo_n_groove said:

Yeah I know. I am quite funny usually. I'll try harder, lol.static111 said:

ah well nuance is lost on the forums more often than nottempo_n_groove said:

Yes, meaning that they were educated. it was an attempt at a joke.static111 said:

lol you asked hugh if he got that information by being surrounded by scholars.tempo_n_groove said:

Common information that you are taught. How about Joe at the office?static111 said:

This is common information that is gone over almost weekly at any construction site, especially in the summer...not exactly scholars but well known among anyone that has worked in trades.tempo_n_groove said:

You must be surrounded by scholars then or give people way more credit than what they deserve.HughFreakingDillon said:

I know. how could any adult not know that?tempo_n_groove said:

I was talking about the darker pee...HughFreakingDillon said:

how could any adult not know that?tempo_n_groove said:

You know how many people don't know that little tidbit?Lerxst1992 said:tempo_n_groove said:

My pee was dark you loon, lol. Sign of dehydration.Halifax2TheMax said:

Why were you peeing in the dark? Did the power go out?tempo_n_groove said:So yesterday I was out in this heat and nearly fell out... I've been riding my bike and drinking what I thought was a good amount of water so I thought I'd be good all day. For working in doors? Sure. For outdoors? Not even close. I downed 4 liters of water in a short period and peed once... And it was dark.

I need to hydrate better,

Be careful out there people.

TMI

Just pointing out that it wasn't always common knowledge..

oooh, umm please dont try, let it fall naturally. you may have more success....

Man, text in certain jokes are just flops...0 -

That vehicle in that pic isn't needed. it's too clean and they might tow a boat on occasion but it's a grocery getter.hedonist said:I see your point, but in reality you have absolutely no idea why this person has the truck or what it’s used for.

So maybe he does need it.

I drive a pick up that I haul tools, camping, kayaks, bikes, friends' crap. So I do use mine for it's intended use and it is a lifesaver come winter. When people shouldn't be on the road I am good to go anywhere.0 -

Maybe so. Maybe he just had it washed too.tempo_n_groove said:

That vehicle in that pic isn't needed. it's too clean and they might tow a boat on occasion but it's a grocery getter.hedonist said:I see your point, but in reality you have absolutely no idea why this person has the truck or what it’s used for.

So maybe he does need it.

I drive a pick up that I haul tools, camping, kayaks, bikes, friends' crap. So I do use mine for it's intended use and it is a lifesaver come winter. When people shouldn't be on the road I am good to go anywhere.

Look, I’m not an apologist, but it riles me when people make assumptions based on “but the truck is too clean”. It’s like someone with a handicapped parking tag getting tsk-ed because they don’t “look like they needed it”.

You just don’t know. And remarkably, that’s fine.0 -

Good thing I was making a generalization based on observations and experience and was not making assumptions! Really gotta watch my ass around this place!

"It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0 -

Australia to protect Barrier Reef by banning coal mineBy ROD McGUIRKYesterday

CANBERRA, Australia (AP) — Australia’s new government announced on Thursday it plans to prevent development of a coal mine due to the potential impact on the nearby Great Barrier Reef.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek said she intends to deny approval for the Central Queensland Coal Project to be excavated northwest of the Queensland state town of Rockhampton.

continues....

_____________________________________SIGNATURE________________________________________________

Not today Sir, Probably not tomorrow.............................................. bayfront arena st. pete '94

you're finally here and I'm a mess................................................... nationwide arena columbus '10

memories like fingerprints are slowly raising.................................... first niagara center buffalo '13

another man ..... moved by sleight of hand...................................... joe louis arena detroit '140 -

mickeyrat said:Australia to protect Barrier Reef by banning coal mineBy ROD McGUIRKYesterday

CANBERRA, Australia (AP) — Australia’s new government announced on Thursday it plans to prevent development of a coal mine due to the potential impact on the nearby Great Barrier Reef.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek said she intends to deny approval for the Central Queensland Coal Project to be excavated northwest of the Queensland state town of Rockhampton.

continues....

Good move!

"It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0 -

Good move by Straya but unfortunately they are one of the worst coal polluters on the planet.

Saying that on a day when Collingwood continues its remarkable run of 11 straight by defeating the defending champs in yet another thrilling last minute AFL victory. A year removed from near last place, bonza I reckon.0 -

Middle aged men got a bit self conscious buying their sports cars when the compensating for a small penis theory gained traction.brianlux said:Lerxst1992 said:Bri, definitely agree with "A child born in 2020 will face a far more hostile world that its grandparents did,” but I disagree we are past the point of no return.

But....we need to end coal now, which may be near impossible. When I talk to independents (those lovingly gas price voters) that's really one of two points that I tell them matters (the other being trump is a murderer of Americans).

So forget electric cars, that tech is at least a decade away from doing anything. This species needs to end coal now.

Yes, ending coal would be a lot of help.

As far as being past the point of no return for global warming (and I would imagine the author means in terms of human time- who knows how many cycles of warming and ice ages the earth has left over the next 4 billion years), I really don't know if anyone knows for absolute certain. I wonder though, if you could anonymously poll the top 100 climate scientists in the world and ask them to honestly say whether or not we have passed that point, what would that poll indicate?Regardless, of course, what is clearly evident is that we need to start acting now. I get discouraged at time like this morning where, when I went to meet some friends in town this morning the only place to park was next to a pickup truck that was too large to fit into a standard parking space (and too clean and shiny to be a work truck). Fortunately, my car easily fit into the crowded space next to it.

Does anyone really need this? I guess they just bought big trucks instead. That theory needs to be modified now

I guess they just bought big trucks instead. That theory needs to be modified now

it actually makes a lot more sense in the context of needing to buy a giant truck and then lifting it to make it even bigger0 -

also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?

_____________________________________SIGNATURE________________________________________________

Not today Sir, Probably not tomorrow.............................................. bayfront arena st. pete '94

you're finally here and I'm a mess................................................... nationwide arena columbus '10

memories like fingerprints are slowly raising.................................... first niagara center buffalo '13

another man ..... moved by sleight of hand...................................... joe louis arena detroit '140 -

mickeyrat said:also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?I hadn't heard that but found this:I have to give kudos to Resenbrink for founding the Green Party but disappointed that the party has remained weak, partly due to lack of good, qualified candidates (some of whom have been down right embarrassing. Their own Green Parties in some other countries (Germany, in particular) have gained better traction.

"It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0 -

In Europe you often govern with a coalitionbrianlux said:mickeyrat said:also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?I hadn't heard that but found this:I have to give kudos to Resenbrink for founding the Green Party but disappointed that the party has remained weak, partly due to lack of good, qualified candidates (some of whom have been down right embarrassing. Their own Green Parties in some other countries (Germany, in particular) have gained better traction.

Green Party hurts democrats in a two party system. I like the Green Party. I would also never waste my vote on them as long as our political system is two main parties

if they progressive wing of the Democratic Party joined the Green Party, neither party could win any election against a Republican

Post edited by Cropduster-80 on0 -

Cropduster-80 said:

In Europe you often govern with a coalitionbrianlux said:mickeyrat said:also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?I hadn't heard that but found this:I have to give kudos to Resenbrink for founding the Green Party but disappointed that the party has remained weak, partly due to lack of good, qualified candidates (some of whom have been down right embarrassing. Their own Green Parties in some other countries (Germany, in particular) have gained better traction.

Green Party hurts democrats in a two party system. I like the Green Party. I would also never waste my vote on them as long as our political system is two main parties

if they progressive wing of the Democratic Party joined the Green Party, neither party could win any election against a RepublicanYeah, sorry to say I have, the times I have voted Green have felt like I had thrown my vote away. But how else can it gain traction? I don't see our two party system as working very well. In fact, I see it as collapsing. But who doesn't these days, right?"It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0 -

If the MAGA wing ever breaks from the Republican Party the greens can break from the democrats.brianlux said:Cropduster-80 said:

In Europe you often govern with a coalitionbrianlux said:mickeyrat said:also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?I hadn't heard that but found this:I have to give kudos to Resenbrink for founding the Green Party but disappointed that the party has remained weak, partly due to lack of good, qualified candidates (some of whom have been down right embarrassing. Their own Green Parties in some other countries (Germany, in particular) have gained better traction.

Green Party hurts democrats in a two party system. I like the Green Party. I would also never waste my vote on them as long as our political system is two main parties

if they progressive wing of the Democratic Party joined the Green Party, neither party could win any election against a RepublicanYeah, sorry to say I have, the times I have voted Green have felt like I had thrown my vote away. But how else can it gain traction? I don't see our two party system as working very well. In fact, I see it as collapsing. But who doesn't these days, right?Seriously though I don’t think it’s possible because of how we elect presidents. 4 people running and you could get a president with like 25 percent support (or even less considering the electoral college). I think it’s easier to swallow when the leader of the biggest party of a governing coalition is the prime minister

or in another way. Someone could just win california or Texas 51-49 and have more electoral votes than any other candidate if there are enough parties on the ballot.. The president has too much power for that to be a good idea when you win the presidency with only 51 percent of California votersPost edited by Cropduster-80 on0 -

Cropduster-80 said:

If the MAGA wing ever breaks from the Republican Party the greens can break from the democrats.brianlux said:Cropduster-80 said:

In Europe you often govern with a coalitionbrianlux said:mickeyrat said:also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?I hadn't heard that but found this:I have to give kudos to Resenbrink for founding the Green Party but disappointed that the party has remained weak, partly due to lack of good, qualified candidates (some of whom have been down right embarrassing. Their own Green Parties in some other countries (Germany, in particular) have gained better traction.

Green Party hurts democrats in a two party system. I like the Green Party. I would also never waste my vote on them as long as our political system is two main parties

if they progressive wing of the Democratic Party joined the Green Party, neither party could win any election against a RepublicanYeah, sorry to say I have, the times I have voted Green have felt like I had thrown my vote away. But how else can it gain traction? I don't see our two party system as working very well. In fact, I see it as collapsing. But who doesn't these days, right?Seriously though I don’t think it’s possible because of how we elect presidents. 4 people running and you could get a president with like 25 percent support (or even less considering the electoral college). I think it’s easier to swallow when the leader of the biggest party of a governing coalition is the prime minister

or in another way. Someone could just win california or Texas 51-49 and have more electoral votes than any other candidate if there are enough parties on the ballot.. The president has too much power for that to be a good idea when you win the presidency with only 51 percent of California votersI think you're right. I don't see us going far with more than two parties. We're very entrenched in our system.My fantasy would be to greatly reduce the power of the presidency. In fact, I would like to see the role of the president be a combination of wise elder/ advisor/ cultural representative/ figurehead and have the real work of running the country done by committee. Giving the president as much power as we do really makes us very nearly an autocracy."It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0 -

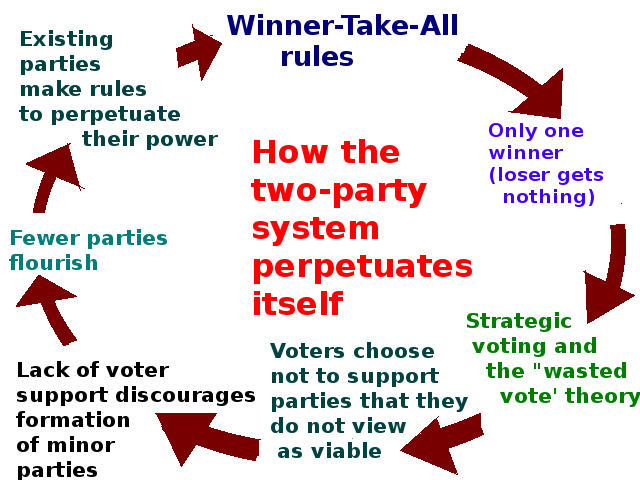

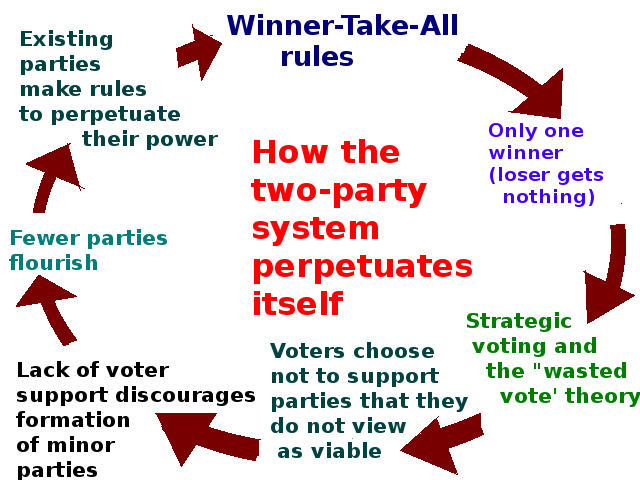

Shamelessly stealing this from Wikipedia because it does such a good job of explaining the vicious cycle of a two-party system.brianlux said:Cropduster-80 said:

In Europe you often govern with a coalitionbrianlux said:mickeyrat said:also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?I hadn't heard that but found this:I have to give kudos to Resenbrink for founding the Green Party but disappointed that the party has remained weak, partly due to lack of good, qualified candidates (some of whom have been down right embarrassing. Their own Green Parties in some other countries (Germany, in particular) have gained better traction.

Green Party hurts democrats in a two party system. I like the Green Party. I would also never waste my vote on them as long as our political system is two main parties

if they progressive wing of the Democratic Party joined the Green Party, neither party could win any election against a RepublicanYeah, sorry to say I have, the times I have voted Green have felt like I had thrown my vote away. But how else can it gain traction? I don't see our two party system as working very well. In fact, I see it as collapsing. But who doesn't these days, right?

'05 - TO, '06 - TO 1, '08 - NYC 1 & 2, '09 - TO, Chi 1 & 2, '10 - Buffalo, NYC 1 & 2, '11 - TO 1 & 2, Hamilton, '13 - Buffalo, Brooklyn 1 & 2, '15 - Global Citizen, '16 - TO 1 & 2, Chi 2

EV

Toronto Film Festival 9/11/2007, '08 - Toronto 1 & 2, '09 - Albany 1, '11 - Chicago 10 -

benjs said:

Shamelessly stealing this from Wikipedia because it does such a good job of explaining the vicious cycle of a two-party system.brianlux said:Cropduster-80 said:

In Europe you often govern with a coalitionbrianlux said:mickeyrat said:also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?I hadn't heard that but found this:I have to give kudos to Resenbrink for founding the Green Party but disappointed that the party has remained weak, partly due to lack of good, qualified candidates (some of whom have been down right embarrassing. Their own Green Parties in some other countries (Germany, in particular) have gained better traction.

Green Party hurts democrats in a two party system. I like the Green Party. I would also never waste my vote on them as long as our political system is two main parties

if they progressive wing of the Democratic Party joined the Green Party, neither party could win any election against a RepublicanYeah, sorry to say I have, the times I have voted Green have felt like I had thrown my vote away. But how else can it gain traction? I don't see our two party system as working very well. In fact, I see it as collapsing. But who doesn't these days, right? There it is in a nutshell, Ben, thanks!So then questions arise like, How do you break this cycle? Can it be broken? Will we ever have the will to change how we do government?"It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0

There it is in a nutshell, Ben, thanks!So then questions arise like, How do you break this cycle? Can it be broken? Will we ever have the will to change how we do government?"It's a sad and beautiful world"-Roberto Benigni0 -

Ironic that when America does nation building they help these countries set up a parliamentary system because a president has too much power.brianlux said:Cropduster-80 said:

If the MAGA wing ever breaks from the Republican Party the greens can break from the democrats.brianlux said:Cropduster-80 said:

In Europe you often govern with a coalitionbrianlux said:mickeyrat said:also saw an article the founder of the green party passed at 93 I think?I hadn't heard that but found this:I have to give kudos to Resenbrink for founding the Green Party but disappointed that the party has remained weak, partly due to lack of good, qualified candidates (some of whom have been down right embarrassing. Their own Green Parties in some other countries (Germany, in particular) have gained better traction.

Green Party hurts democrats in a two party system. I like the Green Party. I would also never waste my vote on them as long as our political system is two main parties

if they progressive wing of the Democratic Party joined the Green Party, neither party could win any election against a RepublicanYeah, sorry to say I have, the times I have voted Green have felt like I had thrown my vote away. But how else can it gain traction? I don't see our two party system as working very well. In fact, I see it as collapsing. But who doesn't these days, right?Seriously though I don’t think it’s possible because of how we elect presidents. 4 people running and you could get a president with like 25 percent support (or even less considering the electoral college). I think it’s easier to swallow when the leader of the biggest party of a governing coalition is the prime minister

or in another way. Someone could just win california or Texas 51-49 and have more electoral votes than any other candidate if there are enough parties on the ballot.. The president has too much power for that to be a good idea when you win the presidency with only 51 percent of California votersI think you're right. I don't see us going far with more than two parties. We're very entrenched in our system.My fantasy would be to greatly reduce the power of the presidency. In fact, I would like to see the role of the president be a combination of wise elder/ advisor/ cultural representative/ figurehead and have the real work of running the country done by committee. Giving the president as much power as we do really makes us very nearly an autocracy.

even Americans who know what they are talking about don’t advocate a presidential system0

Categories

- All Categories

- 149.2K Pearl Jam's Music and Activism

- 110.3K The Porch

- 286 Vitalogy

- 35.1K Given To Fly (live)

- 3.5K Words and Music...Communication

- 39.4K Flea Market

- 39.4K Lost Dogs

- 58.7K Not Pearl Jam's Music

- 10.6K Musicians and Gearheads

- 29.1K Other Music

- 17.8K Poetry, Prose, Music & Art

- 1.1K The Art Wall

- 56.8K Non-Pearl Jam Discussion

- 22.2K A Moving Train

- 31.7K All Encompassing Trip

- 2.9K Technical Stuff and Help