Our Generation: Land. Culture. Freedom.

Byrnzie

Posts: 21,037

This new documentary looks good:

Trailer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/fe ... ilm-review

Our Generation: Land Culture Freedom - review

Sinem Saban and Damien Curtis's documentary examining the state of indigenous rights in Australia offers an insight into years of neglect, ignorance and stereotyping. But it also offers the hope that things could change.

Neil Willis

Guardian Weekly, Monday 14 February 2011

In 2008, Australia's then prime minister, Kevin Rudd, apologised to the country's indigenous population for the "indignity and degradation" to which past governments had subjected them. Although "sorry" was only a simple word, Australia's First Peoples, the Aborigines, the indigenous population, hoped the apology would herald a new era of race relations. Sunday 13 February 2011 was the three-year anniversary of Sorry Day, but in the years since Rudd's announcement it seems little has changed.

Our Generation is a documentary feature from Sinem Saban and Damien Curtis looking at the complex issue of indigenous rights in Australia. The pair have not only the knowledge and understanding to tackle subject, they have the necessary sensitivity to extract an informative and affecting film without getting bogged down in emotion. Saban's academic grounding in Aboriginal Studies has been supplemented by 10 years of work with the Aboriginal community who are the main subject of the film, the Yolngu in Arnhem Land, in the Northern Territory, where she worked as a teacher and human rights activist. Curtis has for a decade worked with tribal peoples around the world to protect their culture and ancestral lands.

The plight of the Aborigine of Australia has been an issue since the colonial flag was first hoisted on Botany Bay. While other colonised indigenous people were at least recognised by treaties with their new governors, no such document was signed on the Bay. The problem of recognition has stayed with the Aborigine ever since.

For all their knowledge and passion for their subject, Saban and Curtis do not lose sight of the fact that their film is the conduit through which the argument for indigenous rights is presented. Many of the civil rights leaders interviewed in the film have been bearing the torch of indigenous rights for years, but years of being ignored by both a conservative media and the governments of John Howard, Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard have taken their toll. Our Generation is very much a call to a new generation of Australians, Aborigine or city-dwelling white suburbanite, to relight the torch and carry it forward.

The testimony of the Yolngu is significant for the film. Aside from Saban's personal connection with the community, they are seen by other Aboriginal groups in Australia as the community that has managed to retain most of its culture, traditions and land. The Yolngu remained stubbornly resistant to most forms of colonisation. Crucially, the community did not cede control of its lands to settlers and managed to retain sovereignty – the issue and importance of which runs throughout the film.

There is much to admire about this documentary, least of all the fact that it was made at all. Curtis and Saban relied on donations to get the project off the ground, but the nature of the independent production meant the film-makers had complete editorial control. The airing of the issues contained therein – racial discrimination, funds for community projects in exchange for land rights – are not addressed in the mainstream media nor can they be found on the political agenda. The result is a film that gives those who contributed a sense of participation ownership over the finished product, especially when their names are included in the credits.

Saban says she was inspired by Michael Moore's documentary Bowling for Columbine, examining the issue of gun ownership in the US. The advance of the documentary format on to mainstream cinema screens has allowed audiences to familiarise themselves with how to watch them. In the case of Saban, like Moore, the idea is to show all of the facts — not just the soundbites given by media or politicians — in a way that spurs the audience into action. Even after the film-making was finished the pair embarked on a national and international promotion, including talks and events, to continue to raise awareness of their subject.

The film works as a traditional piece of cinema because it uses the same blueprint as a traditional linear narrative. The complex issues are laid out in chronological order, from Botany Bay to the current arguments about interventionism, the approach favoured by John Howard's government, which used the media by playing on stereotypes to whip up a moral panic over child abuse and alcoholism in Aboriginal communities. The main protagonists are also laid out for the audience to see. For example, the missionary's paternalistic approach of assimilation — removing children from their families to live with white families, as seen in the Golden Globe-nominated Rabbit-Proof Fence. Not only is this style easy to follow, it is vital in informing the audience of the history of the subject without browbeating them with something akin to a 74-minute political broadcast.

Interviews with young and old Yolngu people, ranging from community leaders to ordinary grandmothers, allows an intriguing look at a culture that is too often overlooked. The Aborigine communities are short on housing and facilities. Health problems mean that life expectancy is far below that enjoyed by their fellow Australians in the cities. Much of the political action has taken aim at the ills of these communities without examining the cause: the current incompatibility of the traditional Aborigine culture, including a more nomadic existence connected to the land, with the more recent western idea of permanent, city-dwelling society. One of the main demands of this documentary is the need, at the very least, for greater integration of these ideals.

Although the film has an agenda of sorts – to both unite First People communities into one voice and encourage that voice to be both used and heard – its main task is to provide a platform for education and action. On the one hand, the film is used to document the misguided policies of the past. However, the effect of the project is to spur a greater number of people to learn about the issue of indigenous rights and demand action be taken. In a similar way to Saban's experience with Bowling for Columbine, audiences should feel compelled to get involved, speak up and eventually force the issue on to the political agenda.

The subject of indigenous rights is a difficult and complex one for modern Australia. It is nagging problem yet to be tackled in the back of a national consciousness. However, facing up to such a subject may stir up emotions long buried or uncover old resentment, guilt or even shame. To a certain degree Kevin Rudd's apology has completed the hardest part. Now the examination of what went wrong and, more importantly, how best to move forward should be the focus.

You can get more information about the issues raised in the film, and buy your own copy of the documentary by going to the Our Generation website at http://www.ourgeneration.org.au

There is a special screening of the film, including a Q&A with the film-makers and a guest appearance by Professor Germaine Greer, on Wednesday 16 February at the Royal Geographical Society, 1 Kensington Gore, London SW7 2AR. Tickets can be booked through the Our Generation website.

Trailer:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/fe ... ilm-review

Our Generation: Land Culture Freedom - review

Sinem Saban and Damien Curtis's documentary examining the state of indigenous rights in Australia offers an insight into years of neglect, ignorance and stereotyping. But it also offers the hope that things could change.

Neil Willis

Guardian Weekly, Monday 14 February 2011

In 2008, Australia's then prime minister, Kevin Rudd, apologised to the country's indigenous population for the "indignity and degradation" to which past governments had subjected them. Although "sorry" was only a simple word, Australia's First Peoples, the Aborigines, the indigenous population, hoped the apology would herald a new era of race relations. Sunday 13 February 2011 was the three-year anniversary of Sorry Day, but in the years since Rudd's announcement it seems little has changed.

Our Generation is a documentary feature from Sinem Saban and Damien Curtis looking at the complex issue of indigenous rights in Australia. The pair have not only the knowledge and understanding to tackle subject, they have the necessary sensitivity to extract an informative and affecting film without getting bogged down in emotion. Saban's academic grounding in Aboriginal Studies has been supplemented by 10 years of work with the Aboriginal community who are the main subject of the film, the Yolngu in Arnhem Land, in the Northern Territory, where she worked as a teacher and human rights activist. Curtis has for a decade worked with tribal peoples around the world to protect their culture and ancestral lands.

The plight of the Aborigine of Australia has been an issue since the colonial flag was first hoisted on Botany Bay. While other colonised indigenous people were at least recognised by treaties with their new governors, no such document was signed on the Bay. The problem of recognition has stayed with the Aborigine ever since.

For all their knowledge and passion for their subject, Saban and Curtis do not lose sight of the fact that their film is the conduit through which the argument for indigenous rights is presented. Many of the civil rights leaders interviewed in the film have been bearing the torch of indigenous rights for years, but years of being ignored by both a conservative media and the governments of John Howard, Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard have taken their toll. Our Generation is very much a call to a new generation of Australians, Aborigine or city-dwelling white suburbanite, to relight the torch and carry it forward.

The testimony of the Yolngu is significant for the film. Aside from Saban's personal connection with the community, they are seen by other Aboriginal groups in Australia as the community that has managed to retain most of its culture, traditions and land. The Yolngu remained stubbornly resistant to most forms of colonisation. Crucially, the community did not cede control of its lands to settlers and managed to retain sovereignty – the issue and importance of which runs throughout the film.

There is much to admire about this documentary, least of all the fact that it was made at all. Curtis and Saban relied on donations to get the project off the ground, but the nature of the independent production meant the film-makers had complete editorial control. The airing of the issues contained therein – racial discrimination, funds for community projects in exchange for land rights – are not addressed in the mainstream media nor can they be found on the political agenda. The result is a film that gives those who contributed a sense of participation ownership over the finished product, especially when their names are included in the credits.

Saban says she was inspired by Michael Moore's documentary Bowling for Columbine, examining the issue of gun ownership in the US. The advance of the documentary format on to mainstream cinema screens has allowed audiences to familiarise themselves with how to watch them. In the case of Saban, like Moore, the idea is to show all of the facts — not just the soundbites given by media or politicians — in a way that spurs the audience into action. Even after the film-making was finished the pair embarked on a national and international promotion, including talks and events, to continue to raise awareness of their subject.

The film works as a traditional piece of cinema because it uses the same blueprint as a traditional linear narrative. The complex issues are laid out in chronological order, from Botany Bay to the current arguments about interventionism, the approach favoured by John Howard's government, which used the media by playing on stereotypes to whip up a moral panic over child abuse and alcoholism in Aboriginal communities. The main protagonists are also laid out for the audience to see. For example, the missionary's paternalistic approach of assimilation — removing children from their families to live with white families, as seen in the Golden Globe-nominated Rabbit-Proof Fence. Not only is this style easy to follow, it is vital in informing the audience of the history of the subject without browbeating them with something akin to a 74-minute political broadcast.

Interviews with young and old Yolngu people, ranging from community leaders to ordinary grandmothers, allows an intriguing look at a culture that is too often overlooked. The Aborigine communities are short on housing and facilities. Health problems mean that life expectancy is far below that enjoyed by their fellow Australians in the cities. Much of the political action has taken aim at the ills of these communities without examining the cause: the current incompatibility of the traditional Aborigine culture, including a more nomadic existence connected to the land, with the more recent western idea of permanent, city-dwelling society. One of the main demands of this documentary is the need, at the very least, for greater integration of these ideals.

Although the film has an agenda of sorts – to both unite First People communities into one voice and encourage that voice to be both used and heard – its main task is to provide a platform for education and action. On the one hand, the film is used to document the misguided policies of the past. However, the effect of the project is to spur a greater number of people to learn about the issue of indigenous rights and demand action be taken. In a similar way to Saban's experience with Bowling for Columbine, audiences should feel compelled to get involved, speak up and eventually force the issue on to the political agenda.

The subject of indigenous rights is a difficult and complex one for modern Australia. It is nagging problem yet to be tackled in the back of a national consciousness. However, facing up to such a subject may stir up emotions long buried or uncover old resentment, guilt or even shame. To a certain degree Kevin Rudd's apology has completed the hardest part. Now the examination of what went wrong and, more importantly, how best to move forward should be the focus.

You can get more information about the issues raised in the film, and buy your own copy of the documentary by going to the Our Generation website at http://www.ourgeneration.org.au

There is a special screening of the film, including a Q&A with the film-makers and a guest appearance by Professor Germaine Greer, on Wednesday 16 February at the Royal Geographical Society, 1 Kensington Gore, London SW7 2AR. Tickets can be booked through the Our Generation website.

Post edited by Byrnzie on

0

Comments

-

Our Generation - Official Trailer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElW6M0hU7jo0

-

This looks Great!, i'm a huge Midnight Oil fan, my first love, this sounds really intresting, having it laid out step by step from the Aborigines point of veiw. You wouldn't by anychance know of something like this about American Natives? (more of my sister's thing).

I don't know why i'm into Aussie history more than American, but i am.0 -

BinauralJam wrote:You wouldn't by anychance know of something like this about American Natives? (more of my sister's thing).

This is a good one - Incident at Oglala - The Leonard Peltier Story

Part One: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W-TzSt4EBcI

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W-TzSt4EBcI

Part Two: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ypAMbGA_i8E Post edited by Byrnzie on0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ypAMbGA_i8E Post edited by Byrnzie on0 -

Byrnzie wrote:BinauralJam wrote:You wouldn't by anychance know of something like this about American Natives? (more of my sister's thing).

This is a good one - Incident at Oglala - The Leonard Peltier Story

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid ... 691110146#

Cool! You are the Man! i'll check this at work tomorrow and forward to She who sha'll not be named.0 -

BinauralJam wrote:This looks Great!, i'm a huge Midnight Oil fan, my first love, this sounds really intresting, having it laid out step by step from the Aborigines point of veiw. You wouldn't by anychance know of something like this about American Natives? (more of my sister's thing).

I don't know why i'm into Aussie history more than American, but i am.

You like Midnight OIL

Did you Know that bands lead singer has been in the current government as minister for the last few years

Do you remember all their songs

about Uranium -HE hasnt done a thing about it

about aboriginals - he hasnt done a thing about it

sang a lot of songs. brow beated the governments

but when he gets in

HE DOES SWEET FUCK ALL

PG is a HYPOCRITEAUSSIE AUSSIE AUSSIE0 -

given a cushy labor seat and sold his soul.hear my name

take a good look

this could be the day

hold my hand

lie beside me

i just need to say0 -

ONCE DEVIDED wrote:BinauralJam wrote:This looks Great!, i'm a huge Midnight Oil fan, my first love, this sounds really intresting, having it laid out step by step from the Aborigines point of veiw. You wouldn't by anychance know of something like this about American Natives? (more of my sister's thing).

I don't know why i'm into Aussie history more than American, but i am.

You like Midnight OIL

Did you Know that bands lead singer has been in the current government as minister for the last few years

Do you remember all their songs

about Uranium -HE hasnt done a thing about it

about aboriginals - he hasnt done a thing about it

sang a lot of songs. brow beated the governments

but when he gets in

HE DOES SWEET FUCK ALL

PG is a HYPOCRITE

Yes I Did, and it breaks my heart. but their were other people in the band who i still put on a pedestal. like Rob Hirst. 0

like Rob Hirst. 0 -

And Byrnzy

MAte the reason aboriginals get a lot of greif from Mainstream Aussies is the amount of handouts that they receive from the government.

also they will go on about the historical significance of a place so that they can claim it as a sacred site. as soon as they get their hands on it they lease it to mining companies for profit.

this pisses a lot of people off

The Gov is creating a massive problem of people reliant on handouts.

instead of creating jobs and futures they just throw cash at the problem.

And unfortunatly a lot ( not all) just take that money and Drink it. and thus the stereotype continues

Sure anglos also have these same problems. But Aboriginals are treated differently.

I work witha few abotiginals at my worksite, from workshop to engineers, they hate this issue. they see themselves as aussie aboriginals. they dont want handouts for their people they want handups.

succesful people who are proud of what they do and are.

My theory is to apologise ( done that) and pay a massive payout to the aboriginal community. then after that they receive the same as everyone else. no extras.

the same

bring on the insultsAUSSIE AUSSIE AUSSIE0 -

ONCE DEVIDED wrote:And Byrnzy

MAte the reason aboriginals get a lot of greif from Mainstream Aussies is the amount of handouts that they receive from the government.

also they will go on about the historical significance of a place so that they can claim it as a sacred site. as soon as they get their hands on it they lease it to mining companies for profit.

this pisses a lot of people off

The Gov is creating a massive problem of people reliant on handouts.

instead of creating jobs and futures they just throw cash at the problem.

And unfortunatly a lot ( not all) just take that money and Drink it. and thus the stereotype continues

Sure anglos also have these same problems. But Aboriginals are treated differently.

I work witha few abotiginals at my worksite, from workshop to engineers, they hate this issue. they see themselves as aussie aboriginals. they dont want handouts for their people they want handups.

succesful people who are proud of what they do and are.

My theory is to apologise ( done that) and pay a massive payout to the aboriginal community. then after that they receive the same as everyone else. no extras.

the same

bring on the insults

They're mostly just drunken scroungers, right?

Maybe, like the Native Americans, there's a difference between Aboriginals who want to be integrated into White society, and Aboriginals who want to be left alone to live their lives the way they choose, free of government interference and without the government constantly looking for ways to steal more of their land?

What's your opinion on the fact that the intervention was based on lies and was motivated by the greed of mining companies to open up valuable tracts of land for uranium, iron ore and zinc?

What's your opinion on the fact that a UN report – State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples – found that Australian Aborigines have the worst life expectancy rates of any indigenous peoples in the world? (In Australia the life expectancy gap is 20 years. In Guatemala it is 13, and in New Zealand it is 11.)

What's your opinion on the fact that the UN special rapporteur on indigenous rights James Aneya, said racism was entrenched in Australia and that the Northern Territory intervention was an attempt to disempower Aborigines?

“It undermines the right of indigenous peoples to control their own destinies, their right to self-determination” - James Aneya

What's ypur opinion on the governments efforts to force them out of meaningful Territory-subsidised employment (CDEP) and force them back onto the dole?

What's your opinion on the Aboriginals being forced to sign over their land to the federal government for 99 years in exchange for housing development?

What's your opinion on the fact that the Australian constitution makes no mention of indigenous people, and that Australia is the only western democracy without a bill of rights?

What's your opinion on the findings of the 'Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination' whose criticisms were that:

* proposed reforms to HREOC that may limit its independence and hinder its effectiveness at monitoring Australia's compliance with the provisions of the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

* the abolition of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), an elected body of indigenous representatives, the main policy-making body in Aboriginal affairs

* a lack of legislation criminalising serious acts or incitement of racial hatred, in the Commonwealth, the State of Tasmania and the Northern Territory

* that no cases of racial discrimination, as distinct from racial hatred, have been successfully litigated in the Federal courts since 2001

* reversal since 1998 of progress made under 1993's Native Title Act and Mabo case, with new legal certainty for government and third parties provided at the expense of indigenous title

* diverging perceptions between governmental authorities and indigenous peoples and others on the compatibility of the 1998 amendments to the Native Title Act with the Convention

* that proof of continuous observance and acknowledgement of the laws and customs of indigenous peoples since the British acquisition of sovereignty over Australia is required to establish native title

* very poor conditions of employment, housing, health, education and income for indigenous Australians, compared with non-indigenous

* mandatory sentencing in Western Australia, which disproportionately impacts indigenous Australians

* the "striking over-representation" of indigenous people in prison, and dying in custody

* that indigenous women are the fastest growing prison population

* that many have been in detention for over three years

* that the Federal Government has rejected most of the recommendations adopted by the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation given in 20000 -

Byrnzy

A lot there to get through so will try to reply in depth later.

firstly though I dont think They are scroungers. Its a bloody big problem. and its a focus for those in australia who are racist ( and their is alot of them)

Its funny how in all those reports their is nothing about how much more you get in this country IF YOU ARE ABORIGINAL. And thus with that issue those racist australians use that as a focus point.

you mentioned that some want to be left alone and live a traditional life. Plenty of space in this country to do just that.

The intervention was based more on the problems revolving oround alchahol and the problemsthat caused, many sober aboriginals in the communities affected are actually happy, more kids are turning up for school.

Im compassionate about the plight many aboriginals face

many live in communities with no work for them, the only shop in the community being a grog shop.

I want everyone white , black and blue to be equal. to have oppertunities to do and be whatever they can be, want to be. IF THAT MEANS taking the grog off their parents so they are sober enough to get their kids to school well maybe thats required.

as I said im very compassionate about the plight of this mighty aboriginal nation. Yes we took their land , yes many bad things have been done in our short history. But we are moving forward sommetimes slowly.

by browbeating australia The UN is getting more and more people to raise their middle finger to them. To many in this country aboriginals get a lot more than others, and it pisses em off no end that they are then told that the aboriginals should have more

I was born here on this great land, So was Jason my good Koori mate 2 years apart

his skin is black mine white , and that should be the only difference.AUSSIE AUSSIE AUSSIE0 -

ONCE DEVIDED wrote:...I was born here on this great land, So was Jason my good Koori mate 2 years apart

his skin is black mine white , and that should be the only difference.

which is really no difference at all. 8-)hear my name

take a good look

this could be the day

hold my hand

lie beside me

i just need to say0 -

Byrnzie wrote:

What's your opinion on the fact that the Australian constitution makes no mention of indigenous people, and that Australia is the only western democracy without a bill of rights?

a bill of rights doesnt necessarily guarantee equal rights. you should know this steve.

australia isnt immune from bigotry and we dont pretend to be. the australian constitution reflects the time in which it was written. a time in which the interests of white male middle-upper class politicians who drafted it were paramount.

in 1967 section 127 of the australian constituition was repealed in order that aboriginal australians be able to be counted in the census as citizens. and therefore as people.

so you see steve there was(though thats not IS, is it?) mention of aborigines in the australian constitution ... but thats not quite what you meant is it?

should the traditional caretakers of this land be recognised in the constitution? i think so. God is and the Queen frequently is mentioned so it stands to reason the indigenous first nations should be. it is the right thing to do imo.hear my name

take a good look

this could be the day

hold my hand

lie beside me

i just need to say0 -

ONCE DEVIDED wrote:Its funny how in all those reports their is nothing about how much more you get in this country IF YOU ARE ABORIGINAL.

So you're saying that Aboriginals are better off than whites?ONCE DEVIDED wrote:many live in communities with no work for them, the only shop in the community being a grog shop.

So which is it? Are they better off than whites, or are the majority of them living in poverty?ONCE DEVIDED wrote:I was born here on this great land, So was Jason my good Koori mate 2 years apart

his skin is black mine white , and that should be the only difference.

Or should it be the only difference?

Aboriginals are different from white Australians. They have their own culture, history, and religious beliefs. Or are you talking about the fact that there should be no difference in terms of equality of the standard of living for those whose traditional way of life has been lost, or taken away from them?0 -

Byrnzie wrote:...

Aboriginals are different from white Australians. They have their own culture, history, and religious beliefs. Or are you talking about the fact that there should be no difference in terms of equality of the standard of living for those whose traditional way of life has been lost, or taken away from them?

aboriginal australians are/were not the only people here who had their own culture history and religious beliefs... and who had that taken from them.

in modern times it is very difficult, if not impossible, for a semi nomadic people to maintain the culture theyve held onto for thousands of years. does this mean we should just roll right over the top of them? no it doesnt. there has to be a balance.. and it has to be a viable balance. and everyone should be treated equally.hear my name

take a good look

this could be the day

hold my hand

lie beside me

i just need to say0 -

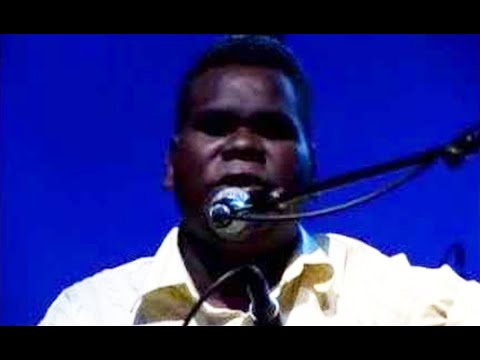

Anyone ever heard this dudes music? He's a blind Australian Aboriginal from the same clan that the above documentary was filmed:

Check it out:

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu - Djarimirri: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bawDFY8G-o4]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bawDFY8G-o4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bawDFY8G-o4]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bawDFY8G-o4

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu - I Was Born Blind: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8B8GQFbEoM Post edited by Byrnzie on0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8B8GQFbEoM Post edited by Byrnzie on0 -

catefrances wrote:there has to be a balance.. and it has to be a viable balance. and everyone should be treated equally.

Yep.

Racial discrimination = not good.0 -

Byrnzie wrote:Anyone ever heard this dudes music? He's a blind Australian Aboriginal from the same clan that the above documentary was filmed:

Check it out:

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu - Djarimirri: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bawDFY8G-o4

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu - I Was Born Blind: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6WI1Afq ... re=related

yes i have.hear my name

take a good look

this could be the day

hold my hand

lie beside me

i just need to say0 -

Byrnzie wrote:catefrances wrote:there has to be a balance.. and it has to be a viable balance. and everyone should be treated equally.

Yep.

Racial discrimination = not good.

ANY discrimination not good.

im kinda curious steve about what you propose we, as a nation do, in order that equality be achieved. youve clearly be reading a bit about australia lately and id like to hear your thoughts on how we go about providing the services needed to those remote aboriginal communities.hear my name

take a good look

this could be the day

hold my hand

lie beside me

i just need to say0 -

catefrances wrote:im kinda curious steve about what you propose we, as a nation do, in order that equality be achieved. youve clearly be reading a bit about australia lately and id like to hear your thoughts on how we go about providing the services needed to those remote aboriginal communities.

I read that in the first 5 years of the intervention - which was supposedly designed to improve living conditions in Aboriginal townships, and where new housing was declared a priority - zero houses were built. Instead, the mining companies moved in and began tearing up the land.

So maybe that should be addressed for a start.

And this looks to be a positive step:

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/na ... 5901336628

Aboriginal communities ask government for drink bans

August 05, 2010

THREE Aboriginal communities around Halls Creek have had stringent new alcohol bans imposed on their lands.

The communities in Halls Creek, one of the country's most troubled remote shires, asked the West Australian government for the bans.

Approving the restrictions yesterday, Racing and Gaming Minister Terry Waldron said fines of up to $5000 would be imposed on licensees and $2000 on anyone else who was caught bringing or possessing alcohol on their lands. Police would also have power to seize or destroy any alcohol they found.

The move brings to 10 the number of remote Aboriginal communities in the west with police-enforceable alcohol bans, with all but one requesting the move voluntarily.

Nine are in the Kimberley and one in the Pilbara.

The alcohol problems in Halls Creek were so severe last year that a ban on selling full-strength takeaway alcohol was imposed on the town, triggering a big drop in assaults, police call-outs and emergency hospital admissions.

The number of incidents attended by police more than halved, and the number of presentations by residents at the local hospital fell 47 per cent.

But significant problems remain, which has prompted the latest move.

Mr Waldron said the 200-strong Ringer Soak (Kundat Djaru) community and smaller Nicholson Block and Koongie Park communities around Halls Creek had approached him for the bans to try to reduce alcohol-related harm and ill-health.

He said it was a credit to them all that they had recognised the threat to personal and social health and chosen to take a stand.

Mr Waldron said that while communities could declare their land dry using their own by-laws, enforcing the rules without government backing was difficult.

Police Commissioner Karl O'Callaghan said police would do their bit to ensure the new bans were enforced.

"Communities that take the initiative to tackle alcohol abuse and the myriad of problems associated with it have my total support and admiration," the Police Commissioner said. "There's an indisputable link between alcohol abuse in remote communities and the level of violence, domestic violence and child welfare issues."

Curtin University professor of health policy Mike Daube said the voluntary bans represented a significant cultural shift that gave hope for the future.

"It's important both in what it will do and symbolically," he said. "The more communities there are, the more it will be seen as Aboriginal people playing a role themselves in tackling this issue."

And also maybe the following could be advocated:

* Continually acknowledge country and the traditional owners in all formal gatherings.

* Write letters to the editor if you see any injustice in our system.

* Lobby to have your kids' schools incorporate more Indigenous history into their curriculum.

* If you run a business, employ Indigenous staff or train an Indigenous apprentice.

* Encourage Local Councils to create and implement policies for Aboriginal representation or employment.

* Create cultural awareness programs.

* Speak up for the rights of Indigenous people.

* Participate in protest marches for Aboriginal rights.

* Get books or the Koori Mail into the library.

* Invite Aboriginal people to do presentations or talks in schools or at community events.

* Watch out that Aboriginal people are consulted.

* Lobby to have the Aboriginal flag flown next to the Australian flag at all times.

Read more: http://www.creativespirits.info/aborigi ... z1EHuoWAys0 -

Happy Australia Day!0

Categories

- All Categories

- 149.1K Pearl Jam's Music and Activism

- 110.3K The Porch

- 284 Vitalogy

- 35.1K Given To Fly (live)

- 3.5K Words and Music...Communication

- 39.4K Flea Market

- 39.4K Lost Dogs

- 58.7K Not Pearl Jam's Music

- 10.6K Musicians and Gearheads

- 29.1K Other Music

- 17.8K Poetry, Prose, Music & Art

- 1.1K The Art Wall

- 56.8K Non-Pearl Jam Discussion

- 22.2K A Moving Train

- 31.7K All Encompassing Trip

- 2.9K Technical Stuff and Help