OTW Missing Women

mickeyrat

Posts: 45,913

was touched on in the Gabby thread and I didnt feel quite right posting this there , so here we are....

By GILLIAN FLACCUS

52 mins ago

YUROK RESERVATION, Calif. (AP) — The young mother had behaved erratically for months, hitchhiking and wandering naked through two Native American reservations and a small town clustered along Northern California’s rugged Lost Coast.

But things escalated when Emmilee Risling was charged with arson for igniting a fire in a cemetery. Her family hoped the case would force her into mental health and addiction services. Instead, she was released over the pleas of loved ones and a tribal police chief.

The 33-year-old college graduate — an accomplished traditional dancer with ancestry from three area tribes — was last seen soon after, walking across a bridge near a place marked End of Road, a far corner of the Yurok Reservation where the rutted pavement dissolves into thick woods.

A picture of missing woman Emmilee Risling sits on a table at the Risling family home on Jan. 21, 2022, in McKinleyville, Calif. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard)

Her disappearance is one of five instances in the past 18 months where Indigenous women have gone missing or been killed in this isolated expanse of Pacific coastline between San Francisco and Oregon, a region where the Yurok, Hupa, Karuk, Tolowa and Wiyot people have coexisted for millennia. Two other women died from what authorities say were overdoses despite relatives’ questions about severe bruises.

The crisis has spurred the Yurok Tribe to issue an emergency declaration and brought increased urgency to efforts to build California’s first database of such cases and regain sovereignty over key services.

“I came to this issue as both a researcher and a learner, but just in this last year, I knew three of the women who have gone missing or were murdered — and we shared so much in common,” said Blythe George, a Yurok tribal member who consults on a project documenting the problem. “You can’t help but see yourself in those people.”

___

Yurok Tribal Police Chief Greg O'Rourke visits the last confirmed location on Jan. 19, 2022, where Emmilee Risling was seen before going missing in October 2021, in Klamath, Calif. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard)

The recent cases spotlight an epidemic that is difficult to quantify but has long disproportionately plagued Native Americans.

A 2021 report by a government watchdog found the true number of missing and murdered Indigenous women is unknown due to reporting problems, distrust of law enforcement and jurisdictional conflicts. But Native women face murder rates almost three times those of white women overall — and up to 10 times the national average in certain locations, according to a 2021 summary of the existing research by the National Congress of American Indians. More than 80% have experienced violence.

In this area peppered with illegal marijuana farms and defined by wilderness, almost everyone knows someone who has vanished.

Yurok Tribal Police Chief Greg O'Rourke drives through the Yurok Reservation while revisiting the sites where Emmilee Risling was last seen, Jan. 19, 2022, in Klamath, Calif. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard)

Missing person posters flutter from gas station doors and road signs. Even the tribal police chief isn’t untouched: He took in the daughter of one missing woman, and Emmilee — an enrolled Hoopa Valley tribal member with Yurok and Karuk blood — babysat his children.

In California alone, the Yurok Tribe and the Sovereign Bodies Institute, an Indigenous-run research and advocacy group, uncovered 18 cases of missing or slain Native American women in roughly the past year — a number they consider a vast undercount. An estimated 62% of those cases are not listed in state or federal databases for missing persons.

Hupa citizen Brandice Davis attended school with the daughters of a woman who disappeared in 1991 and now has daughters of her own, ages 9 and 13.

“Here, we’re all related, in a sense,” she said of the place where many families are connected by marriage or community ties.

She cautions her daughters about what it means to be female, Native American and growing up on a reservation: “You’re a statistic. But we have to keep going. We have to show people we’re still here.”

Maile Kane, 13, left and her sister Gracie Kane, 9, jump on a trampoline outside their home on Jan. 20, 2022, in Hoopa, Calif. The girl's mother, Brandice Davis, said she grew up with the missing woman Emmilee Risling and worries about the safety of her own daughters. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard)

___

Like countless cases involving Indigenous women, Emmilee’s disappearance has gotten no attention from the outside world.

But many here see in her story the ugly intersection of generations of trauma inflicted on Native Americans by their white colonizers, the marginalization of Native peoples and tribal law enforcement’s lack of authority over many crimes committed on their land.

Virtually all of the area’s Indigenous residents, including Emmilee, have ancestors who were shipped to boarding schools as children and forced to give up their language and culture as part of a federal assimilation campaign. Further back, Yurok people spent years away from home as indentured servants for colonizers, said Judge Abby Abinanti, the tribe’s chief judge.

The trauma caused by those removals echoes among the Yurok in the form of drug abuse and domestic violence, which trickles down to the youth, she said. About 110 Yurok children are in foster care.

“You say, ‘OK, how did we get to this situation where we’re losing our children?’” said Abinanti. “There were big gaps in knowledge, including parenting, and generationally those play out.”

Abby Abinanti, chief judge of the Yurok Tribal Court, talks about improvements to the tribal court system which she hopes could prevent cases like the disappearance of Emmilee Risling on Jan. 20, 2022, in Klamath, Calif. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard)

An analysis of cases by the Yurok and Sovereign Bodies found most of the region’s missing women had either been in foster care themselves or had children taken from them by the state. An analysis of jail bookings also showed Yurok citizens in the two-county region are 11 times more likely to go to jail in a given year — and half those arrested are female, usually for low-level crimes. That’s an arrest rate for Yurok women roughly five times the rate of female incarcerations nationwide, said George, the University of California, Merced sociologist consulting with the tribe.

The Yurok run a tribal wellness court for addiction and operate one of the country’s only state-certified tribal domestic violence perpetrator programs. They also recently hired a tribal prosecutor, another step toward building an Indigenous justice system that would ultimately handle all but the most serious felonies.

The Yurok also are working to reclaim supervision over foster care and hope to transfer their first foster family from state court within months, said Jessica Carter, the Yurok Tribal Court director. A tribal-run guardianship court follows another 50 children who live with relatives.

The long-term plan — mostly funded by grants — is a massive undertaking that will take years to accomplish, but the Yurok see regaining sovereignty over these systems as the only way to end the cycle of loss that’s taken the greatest toll on their women.

“If we are successful, we can use that as a gift to other tribes to say, ‘Here’s the steps we took,’” said Rosemary Deck, the newly hired tribal prosecutor. “‘You can take this as a blueprint and assert your own sovereignty.’”

Students at Trinidad Elementary School use shadow puppets to tell the traditional Yurok story of a little bird seeking refuge on Jan. 19, 2022, in Trinidad, Calif. Schools near the Yurok reservation have begun teaching tribal and non-tribal students alike about their peoples' history as part of a plan to reinforce cultural roots with the tribes youngest members. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard)

___

Emmilee was born into a prominent Native family, and a bright future beckoned.

Starting at a young age, she was groomed to one day lead the intricate dances that knit the modern-day people to generations of tradition nearly broken by colonization. Her family, a “dance family,” has the rare distinction of owning enough regalia that it can outfit the brush, jump and flower dances without borrowing a single piece.

At 15, Emmilee paraded down the National Mall with other tribal members at the opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. The Washington Post published a front-page photo of her in a Karuk dress of dried bear grass, a woven basket cap and a white leather sash adorned with Pileated woodpecker scalps.

The straight-A student earned a scholarship to the University of Oregon, where she helped lead a prominent Native students' group. Her success, however, was darkened by the first sign of trouble: an abusive relationship with a Native man whom, her mother believes, she felt she could save through her positive influence.

Later, Emmilee dated another man, became pregnant and returned home to have the baby before finishing her degree.

She then worked with disadvantaged Native families and eventually got accepted into a master’s program. She helped coach her son’s T-ball team and signed him up for swim lessons.

In this 2014 photo provided by Gary Risling, Emmilee Risling, right, poses after her graduation from the University of Oregon in Eugene, Ore., with her great-aunt and adoptive grandmother Viola Risling-Ryerson. (Gary Risling via AP)

But over time, her family says, they noticed changes.

Emmilee was uncharacteristically tardy for work and grew more combative. She often dropped off her son with family, and she fell in with another abusive boyfriend. Her son was removed from her care when he was 5; a girl born in 2020 was taken away as a newborn as Emmilee’s behavior deteriorated.

Her parents remain bewildered by her rapid decline and think she developed a mental illness — possibly postpartum psychosis — compounded by drugs and the trauma of domestic abuse. At first, she would see a doctor or therapist at her family’s insistence but eventually rebuffed all help.

After her daughter’s birth, Emmilee spiraled rapidly, “like a light switched,” and she began to let go of the Native identity that had been her defining force, said her sister, Mary.

“That was her life, and when you let that go, when you don’t have your kids ... what are you?” she said.

Mary Risling stands near a photo of her missing sister, Emmilee Risling, at the family home on Jan. 21, 2022, in McKinleyville, Calif. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard)

___

In the months before she vanished, Emmilee was frequently seen walking naked in public, talking to herself. She was picked up many times by sheriff’s deputies and tribal police but never charged.

The only in-patient psychiatric facility within 300 miles (480 kilometers) was always too full to admit her. Once, she was taken to the emergency room and fled barefoot in her hospital gown.

“People tended to look the other way. They didn’t really help her. In less than 24 hours, she was just back on the street, literally on the street,” said Judy Risling, her mother. “There were just no services for her.”

In September, Emmilee was arrested after she was found dancing around a small fire in the Hoopa Valley Reservation cemetery.

Then-Hoopa Valley Tribal Police Chief Bob Kane appeared in a Humboldt County court by video and explained her repeated police contacts and mental health problems. Emmilee mumbled during the hearing then shouted out that she didn’t set the fire.

She was released with an order to appear again in 12 days after her public defender argued she had no criminal convictions and the court couldn’t hold her on the basis of her mental health.

Then, Emmilee disappeared.

“We had predicted that something like this may ... happen in the future,” said Kane. “And you know, now we’re here.”

____

If Emmilee fell through the cracks before she went missing, she has become even more invisible in her absence.

One of the biggest hurdles in Indian Country once a woman is reported missing is unraveling a confusing jumble of federal, state, local and tribal agencies that must coordinate. Poor communication and oversights can result in overlooked evidence or delayed investigations.

The problem is more acute in rural regions like the one where Emmilee disappeared, said Abigail Echo-Hawk, citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and director of the Urban Indian Health Institute in Seattle.

“Particularly in reservations and in village areas, there is a maze of jurisdictions, of policies, of procedures of who investigates what,” she said.

Moreover, many cases aren’t logged in federal missing persons databases, and medical examiners sometimes misclassify Native women as white or Asian, said Gretta Goodwin, of the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s homeland security and justice team.

Recent efforts at the state and federal level seek to address what advocates say have been decades of neglect regarding missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Former President Donald Trump signed a bill that required federal, state, tribal and local law enforcement agencies to create or update their protocols for handling such cases. And in November, President Joe Biden signed an executive order to set up guidelines between the federal government and tribal police that would help track, solve and prevent crimes against all Native Americans.

A number of states, including California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona, are also taking on the crisis with greater funding to tribes, studies of the problem or proposals to create Amber Alert-style notifications.

A pedestrian walks near End of Road on Jan. 19, 2022, where Emmilee Risling was last seen before going missing in October 2021, in Klamath, Calif. (AP Video/Nathan Howard)

___

continues......

_____________________________________SIGNATURE________________________________________________

Not today Sir, Probably not tomorrow.............................................. bayfront arena st. pete '94

you're finally here and I'm a mess................................................... nationwide arena columbus '10

memories like fingerprints are slowly raising.................................... first niagara center buffalo '13

another man ..... moved by sleight of hand...................................... joe louis arena detroit '14

Not today Sir, Probably not tomorrow.............................................. bayfront arena st. pete '94

you're finally here and I'm a mess................................................... nationwide arena columbus '10

memories like fingerprints are slowly raising.................................... first niagara center buffalo '13

another man ..... moved by sleight of hand...................................... joe louis arena detroit '14

0

Comments

-

.Post edited by Spunkie onI was swimming in the Great Barrier Reef

Animals were hiding behind the Coral

Except for little Turtle

I could swear he's trying to talk to me

Gurgle Gurgle0 -

Washington OKs 1st statewide missing Indigenous people alertBy GILLIAN FLACCUS and TED S. WARRENToday

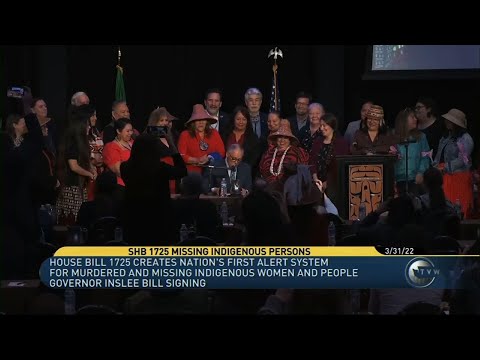

TULALIP, Wash. (AP) — Washington Gov. Jay Inslee on Thursday signed into law a bill that creates a first-in-the-nation statewide alert system for missing Indigenous people, to help address a silent crisis that has plagued Indian Country in this state and nationwide.

The law sets up a system similar to Amber Alerts and so-called silver alerts, which are used respectively for missing children and vulnerable adults in many states. It was spearheaded by Democratic Rep. Debra Lekanoff, the only Native American lawmaker currently serving in the Washington state Legislature, and championed by Indigenous leaders statewide.

“I am proud to say that the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s and People’s Alert System came from the voices of our Native American leaders,” said Lekanoff, a member of the Tlingit tribe and the bill’s chief sponsor. “It’s not just an Indian issue, it’s not just an Indian responsibility. Our sisters, our aunties, our grandmothers are going missing every day ... and it’s been going on for far too long.”

Tribal leaders, many of them women, wore traditional hats woven from cedar as they gathered around Inslee for the signing on the Tulalip Reservation, north of Seattle. Afterward they gifted him with a handmade traditional ribbon shirt and several multicolored woven blankets.

The law attempts to address a crisis of missing Indigenous people — particularly women — in Washington and across the United States. While it includes missing men, women and children, a summary of public testimony on the legislation notes that “the crisis began as a women’s issue, and it remains primarily a women’s issue.”

Besides notifying law enforcement when there’s a report of a missing Indigenous person, the new alert system will place messages on highway reader boards and on the radio and social media, and provide information to the news media.

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee on Thursday signed into law a bill that creates a first-in-the-nation statewide alert system for missing Indigenous people, to help address a silent crisis that has plagued Indian Country in this state and nationwide. (March 31)

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee on Thursday signed into law a bill that creates a first-in-the-nation statewide alert system for missing Indigenous people, to help address a silent crisis that has plagued Indian Country in this state and nationwide. (March 31)The legislation was paired with another bill Inslee, a Democrat, signed Thursday that requires county coroners or medical examiners to take steps to identify and notify family members of murdered Indigenous people and return their remains. That new law also establishes two grant funds for Indigenous survivors of human trafficking.

This piece of the crisis is important because in many cases, murdered Indigenous women are mistakenly recorded as white or Hispanic by coroners' offices, they're never identified, or their remains never repatriated.

A 2021 report by the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office found the true number of missing and murdered Indigenous women in the U.S. is unknown due to reporting problems, distrust of law enforcement and jurisdictional conflicts. But Native American women face murder rates almost three times those of white women overall — and up to 10 times the national average in certain locations, according to a 2021 summary of the existing research by the National Congress of American Indians. More than 80% have experienced violence.

In Washington, more than four times as many Indigenous women go missing than white women, according to research conducted by the Urban Indian Health Institute in Seattle, but many such cases receive little or no media attention.

The bill signing began with a traditional welcome song passed down by Harriette Shelton Dover, a cherished cultural leader and storyteller. Dover recovered and shared many traditions and songs from tribes along Washington's northern Pacific Coast and worked with linguists before her death in 1991 to preserve her language, Lushootseed, from extinction. Women performed an honor song after the event.

Tulalip Tribes of Washington Chairwoman Teri Gobin said Washington and Montana are the two states with the most missing Indigenous people in the U.S. Nearly four dozen Native people are currently missing in Seattle alone, she said.

“What’s the most important thing is bringing them home, whether they’ve been trafficked, whether they’ve been stolen or murdered,” she said. “It’s a wound that stays open, and it’s something that we pray with (for) each person, we can bring them home."

Investigations into missing Indigenous people, particularly women, have been plagued by many issues for decades.

When a person goes missing on a reservation, there are often there are jurisdictional conflicts between tribal police and local and state law enforcement. A lack of staff and police resources, and the rural nature of many reservations, compound those problems. And many times, families of tribal members distrust non-Native law enforcement or don't know where to report news of a missing loved one.

An alert system will help mitigate some of those problems by allowing better communication and coordination between tribal and non-tribal law enforcement and creating a way for law enforcement to flag such cases for other agencies. The law expands the definition of “missing endangered person” to include Indigenous people, as well as children and vulnerable adults with disabilities or memory or cognitive issues.

The law takes effect June 9 and some details are still being worked out. For example, it's unclear what criteria law enforcement will use to positively identify a missing person as Native American and how the information will be disseminated in rural areas, including on some reservations, where highways lack electronic reader boards — or where there aren't highways at all.

The measure is the latest step Washington has taken to address the issue. The Washington State Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People Task Force is working to coordinate a statewide response and had its first meeting in December. Its first report is expected in August.

Many states from Arizona to Oregon to Wisconsin have taken recent action to address the crisis of murdered and missing Indigenous women. Efforts include funding for better resources for tribal police to the creation of new databases specifically targeting missing tribal members. Tribal police agencies that use Amber Alerts for missing Indigenous children include the Hopi and Las Vegas Paiute.

In California, the Yurok Tribe and the Sovereign Bodies Institute, an Indigenous-run research and advocacy group, uncovered 18 cases of missing or slain Native American women in roughly the past year in their recent work — a number they consider a vast undercount. An estimated 62% of those cases are not listed in state or federal databases for missing persons.

continues. ......

_____________________________________SIGNATURE________________________________________________

Not today Sir, Probably not tomorrow.............................................. bayfront arena st. pete '94

you're finally here and I'm a mess................................................... nationwide arena columbus '10

memories like fingerprints are slowly raising.................................... first niagara center buffalo '13

another man ..... moved by sleight of hand...................................... joe louis arena detroit '140 -

-

Prolly lost n gone foreverI was swimming in the Great Barrier Reef

Animals were hiding behind the Coral

Except for little Turtle

I could swear he's trying to talk to me

Gurgle Gurgle0 -

doesnt exactly fit the topic but.....Canada’s Indigenous women forcibly sterilized decades after other rich countries stopped By Maria Cheng Today TORONTO (AP) — Decades after many other rich countries stopped forcibly sterilizing Indigenous women, numerous activists, doctors, politicians and at least five class-action lawsuits say the practice has not ended in Canada. A Senate report last year concluded “this horrific practice is not confined to the past, but clearly is continuing today.” In May, a doctor was penalized for forcibly sterilizing an Indigenous woman in 2019. Indigenous leaders say the country has yet to fully reckon with its troubled colonial past — or put a stop to a decades-long practice that is considered a type of genocide. There are no solid estimates on how many women are still being sterilized against their will or without their knowledge, but Indigenous experts say they regularly hear complaints about it. Sen. Yvonne Boyer, whose office is collecting the limited data available, says at least 12,000 women have been affected since the 1970s. “Whenever I speak to an Indigenous community, I am swamped with women telling me that forced sterilization happened to them,” Boyer, who has Indigenous Metis heritage, told The Associated Press. Medical authorities in Canada’s Northwest Territories issued a series of punishments in May in what may be the first time a doctor has been sanctioned for forcibly sterilizing an Indigenous woman, according to documents obtained by the AP. The case involves Dr. Andrew Kotaska, who performed an operation to relieve an Indigenous woman's abdominal pain in November 2019. He had her written consent to remove her right fallopian tube, but the patient, an Inuit woman, had not agreed to the removal of her left tube; losing both would leave her sterile. Despite objections from other medical staff during the surgery, Kotaska took out both fallopian tubes. The investigation concluded there was no medical justification for the sterilization, and Kotaska was found to have engaged in unprofessional conduct. Kotaska's “severe error in surgical judgment” was unethical, cost the patient the chance to have more children and could undermine trust in the medical system, investigators said. The case was likely not exceptional. Thousands of Indigenous Canadian women over the past seven decades were coercively sterilized, in line with eugenics legislation that deemed them inferior. In the U.S., forced sterilizations of Native American women mostly ended in the 1970s after new regulations were adopted requiring informed consent. The Geneva Conventions describe forced sterilization as a type of genocide and crime against humanity and the Canadian government has condemned reports of forced sterilization elsewhere, including among Uyghur women in China. In 2018, the U.N. Committee Against Torture told Canada it was concerned about persistent reports of forced sterilization, saying all allegations should be investigated and those found responsible held accountable. In 2019, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau acknowledged that the murders and disappearances of Indigenous women across Canada amounted to “genocide,” but activists say little has been done to address ingrained prejudices against the Indigenous, allowing forced sterilizations to continue. In a statement, the Canadian government told the AP it was aware of allegations that Indigenous women were forcibly sterilized and the matter is before the courts. “Sterilization of women without their informed consent constitutes an assault and is a criminal offense,” the government said. “We recognize the pressing need to end this practice across Canada,” it said, adding that it is working with provincial and territorial authorities, health agencies and Indigenous groups to eliminate systemic racism in the country's health systems. Boyer, the senator collecting data on the issue, recalled once being approached by a tearful Indigenous woman describing her forced sterilization. “It made my knees buckle to hear her story and to realize how common it was,” Boyer said. "Nothing has changed legally or culturally in Canada to stop this.” ___ Indigenous people comprise about 5% of Canada’s nearly 40 million people, with the biggest populations residing in the north: Nunavut, Yukon and the Northwest Territories. The more than 600 Indigenous communities, known as First Nations, face significant health challenges compared to other Canadians. Suicide rates among Indigenous youth are six times higher than their counterparts and the life expectancy of First Nations people is about 14 years less than other Canadians. Until the 1990s, Indigenous people were mostly treated in racially segregated hospitals, where there were reports of rampant abuse. It’s difficult to say how common sterilization — with or without consent — happens. Canada's national health agency doesn't routinely collect sterilization data, including the ethnicity of patients or under what conditions it happens. In 2019, Sylvia Tuckanow told the Senate committee investigating forced sterilizations about how she gave birth in a Saskatoon hospital in July 2001. She described being disoriented from medication and being tied to a bed as she cried. “I could smell something burning,” she said. “When the (doctor) was finished, he said, ‘There: tied, cut and burnt. Nothing will get through that,’” Tuckanow said, referring to her singed fallopian tubes. She said she hadn’t consented to the procedure. The Senate committee's work was prompted by a previous 2016 investigation led by Sen. Boyer into about a dozen forced sterilizations of Indigenous women at a Saskatchewan hospital. In November, a report documented nearly two dozen forced sterilizations in Quebec from 1980 to 2019, including one woman who said her doctor told her after bladder surgery that he had removed her uterus at the same time — without her consent. The report concluded that doctors and nurses “insistently questioning whether a First Nations or Inuit mother wants to (be sterilized) after the birth of her first child seems to be an existing practice in Quebec.” Some women were not even aware they were sterilized. Morningstar Mercredi, an Alberta-based Indigenous author, was sterilized as a 14-year-old, but didn’t find out until decades later when she sought help after being unable to conceive. “I went into a catatonic stage and had a nervous breakdown,” Mercredi wrote in her 2021 book, “Sacred Bundles Unborn.” She told the AP the cost to First Nations peoples of coerced sterilizations was “staggering,” noting the procedures were previously routine in Indigenous residential schools and hospitals. “These many generations of Indigenous persons denied life is an effective genocide,” she said. The Senate report on forced sterilization made 13 recommendations, including compensating victims, measures to address systemic racism in health care and a formal apology. In response to questions from the AP, the Canadian government said it has taken steps to try to stop forced sterilization, including investing more than 87 million Canadian dollars ($65 million) to improve access to “culturally safe” health services, one-third of which supports Indigenous midwifery initiatives. Last year, the government allocated 6.2 million Canadian dollars ($4.7 million) to help survivors of forced sterilization. It said the Senate report was “further evidence of a broader need to eliminate racism” and acknowledged that bias in the health system “continues to have catastrophic effects on First Nations, Inuit and Metis communities.” ____ Dr. Alika Lafontaine, the first Indigenous president of the Canadian Medical Association, recalls times in his own training when it was unclear whether Indigenous women had agreed to sterilization. “In my residency, there were situations where we would do C-sections on patients and someone would lean over and say, ‘So we’ll also clip her (fallopian) tubes,’” he said. “It never crossed my mind whether these patients had an informed conversation" about sterilization, he said, adding he assumed that had happened before patients were on the operating table. One problem, Lafontaine said, is that many First Nations women must fly hundreds of miles south to deliver their babies. “That happens because we literally did not build any health facilities where Indigenous people live,” he said. Gerri Sharpe, president of Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, said health centers serving Inuit women often aren’t staffed by Indigenous people, resulting in translation problems. For example, in Inuit culture, people often communicate with facial expressions, like raising their eyebrows for “yes” or wrinkling their nose for “no.” “Doctors will be speaking, and they look to the woman to acknowledge something. When she (raises her eyebrows), the doctor labels it as ‘non-responsive,’” Sharpe said. Dr. Ewan Affleck, who made a 2021 film, “ The Unforgotten,” about the pervasive racism against Canada's Indigenous people, said the way forced sterilization happens now is more subtle than in the past. He noted an ongoing “power imbalance” in the country's health system. “If you have a white doctor saying to an Indigenous woman, ‘You should be sterilized,’ it may very likely happen,” he said. ___ There are at least five class-action lawsuits against health, provincial and federal authorities involving forced sterilizations in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Quebec, British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario and elsewhere. May Sarah Cardinal, the representative plaintiff in the Alberta case, said she was pressured into having her tubes tied after having her second child in 1977, but the doctor never explained the procedure was irreversible. “The doctor told me: ‘There are hard times ahead and how are you going to look after a bunch of kids? What if your husband leaves?’” Cardinal told the AP. “I was afraid if I didn’t go through with it, they would be angry with me, and I didn’t feel like I had a say.” Cardinal only realized she had been a victim of forced sterilization when her daughter, Anita, pieced it together after watching a video in a university class about eugenics and forced sterilization. “My mother had always told me she wanted more children but that she didn’t have a choice,” Anita Cardinal said. May Sarah Cardinal said she recalled her doctor asking if she and her husband were “native” Canadians and wondered why that should make a difference. “I would see mothers with their kids and my heart ached not to be able to have more,” she said. —- Kotaska, the ob-gyn who carried out the surgery that left an Indigenous woman sterile in 2019, was the president of the Northwest Territories’ medical association and held teaching positions at several Canadian universities. Documents show an anesthetist and surgical nurse became alarmed when Kotaska said during the surgery to remove the woman's right fallopian tube: “Let’s see if I can find a reason to take the left tube as well." Kotaska told investigators he was “voicing his thought process out loud” that removing both tubes would lessen the woman’s pelvic pain, the documents say. Describing Kotaska’s actions as “a violation of his ethical obligations,” investigators suspended Kotaska’s medical license for five months, ordered him to take an ethics course and reimburse the cost of the inquiry. The Northwest Territories health department said it was the first time a “non-consensual medical procedure” had been referred for investigation. The woman is suing Kotaska and hospital authorities for 6 million Canadian dollars ($4.38 million). There was no suggestion in the documents that Kotaska was motivated by racism. Kotaska declined to comment to the AP. The Canadian government would not comment on Kotaska's actions but said forced sterilization is illegal and prosecutable under Canadian criminal law. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police in the Northwest Territories said there is no criminal investigation into Kotaska. “People don’t want to believe things like this are happening in Canada, but cases like this explain why entire First Nations populations still feel unsafe,” said Dr. Unjali Malhotra, medical officer of the First Nations Health Authority in British Columbia. Despite Canada's reputation as a progressive society, its continued forced sterilization of Indigenous women puts it alongside countries like India and China, where the practice mostly affects women from ethnic minorities. In Europe, forced sterilizations affected more than 90,000 Roma women in past decades in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria. Court rulings, apologies from the governments, reparations programs and modified health policies have mostly stamped out the practice; the last known forced sterilization on the continent was in 2012. In 1976, the U.S. found that forced sterilizations happened in at least one-third of the regions where the government provided health services to Native Americans. The U.S. government has never formally apologized or offered compensation. Indigenous leaders in Canada say an official apology would be a critical step towards rebuilding the country's fractured relationship with First Nations people. Only the province of Alberta has apologized and offered some compensation to those affected before 1972. Mercredi said she continues to endure the repercussions of being sterilized without her knowledge decades ago. “Those who subject women to this must be held accountable,” she said. “No amount of therapy or healing can reconcile the fact that my human right to have children was taken from me.” ___ The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content. ___ This story has been corrected to show Dr. Unjali Malhotra’s title is medical officer, not chief medical officer._____________________________________SIGNATURE________________________________________________

Not today Sir, Probably not tomorrow.............................................. bayfront arena st. pete '94

you're finally here and I'm a mess................................................... nationwide arena columbus '10

memories like fingerprints are slowly raising.................................... first niagara center buffalo '13

another man ..... moved by sleight of hand...................................... joe louis arena detroit '140 -

I'm getting really frustrated so I'm just going to ask out loud: what does OTW mean? I can't find the acronym spellout anywhere, and I feel like I should be able to figure it out on my own.Your boos mean nothing to me, for I have seen what makes you cheer0

-

HughFreakingDillon said:I'm getting really frustrated so I'm just going to ask out loud: what does OTW mean? I can't find the acronym spellout anywhere, and I feel like I should be able to figure it out on my own.

created when that gabby woman was missing. so much emphasis on young pretty white women and girls , I hoped to shine a small light on Other Than White women....

_____________________________________SIGNATURE________________________________________________

Not today Sir, Probably not tomorrow.............................................. bayfront arena st. pete '94

you're finally here and I'm a mess................................................... nationwide arena columbus '10

memories like fingerprints are slowly raising.................................... first niagara center buffalo '13

another man ..... moved by sleight of hand...................................... joe louis arena detroit '140 -

OTHER THAN WHITE. thank you.Your boos mean nothing to me, for I have seen what makes you cheer0

-

Current BC lawsuits are going further and adding indigenous non consent abortions along with sterilization.

Edit to include link: https://www.murphybattista.com/practice-areas/class-action-lawsuits/forced-sterilization-and-abortion-class-action/#:~:text=The Claim alleges that the,authorized and performed by thePost edited by Spunkie onI was swimming in the Great Barrier Reef

Animals were hiding behind the Coral

Except for little Turtle

I could swear he's trying to talk to me

Gurgle Gurgle0

Categories

- All Categories

- 149.1K Pearl Jam's Music and Activism

- 110.3K The Porch

- 284 Vitalogy

- 35.1K Given To Fly (live)

- 3.5K Words and Music...Communication

- 39.4K Flea Market

- 39.4K Lost Dogs

- 58.7K Not Pearl Jam's Music

- 10.6K Musicians and Gearheads

- 29.1K Other Music

- 17.8K Poetry, Prose, Music & Art

- 1.1K The Art Wall

- 56.8K Non-Pearl Jam Discussion

- 22.2K A Moving Train

- 31.7K All Encompassing Trip

- 2.9K Technical Stuff and Help